Hi Anthony, and welcome to The Book Muse.

First, I really enjoy your historical fiction books, and have read a few. What is it about historical books and historical fiction that interests you?

From childhood I have always been fond of history and stories from the past. As a journalist for some 40 years my interest has necessarily been with the world around me and how it came to be. What events from the past shaped today’s society … our outlook, sense of place, social and political values? As a novelist I am deeply involved with individual men and women – their emotions, desires and motivations. The techniques of historical fiction allow me to explore all these facets of human society in a way that is both personal and true to the facts so far as I can determine them.

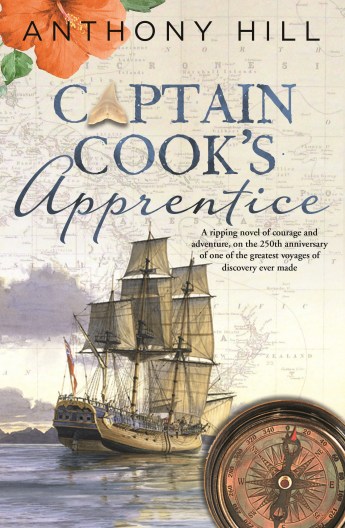

Previously you’ve written books set during World War One – Young Digger, Soldier Boy and Animal Heroes about animals throughout all the wars that Australia has been involved in. What inspired you to write Isaac’s story this time?

I’ve written five military novels about Australians and their involvement in the First and Second World Wars, and I think that’s enough. I’ve nothing more to say on the subject – although if the right story came along I might well have another look at it… In a sense Captain Cook’s Apprenticeis a military novel since it concerns the Royal Navy, but it is of course much more than that. The Endeavour voyage was a pivotal event in the history of our nation and the region we inhabit. It opened the Pacific to European trade, incursion and settlement for both good and ill. I’d long wanted to write about it with the immediacy it would have had to people at the time – and finding Isaac Manley mentioned briefly in Beaglehole’s Life of Cook gave me a way into it. He was a servant boy on the ship making his first voyage. Everything was new to him. He rose to become an Admiral and lived to the ripe age of 82, long enough to see some of the consequences of that voyage bear fruit with settlements in faraway places that he was among the first Europeans to see as a boy.

I learnt the basics of the Endeavourvoyage of 1770 at school – and this book delved into it a bit more and gave it some more depth and character, making it much more interesting. Is it your hope that it will do this for other Australians and history students?

Yes, this is exactly my hope. The great thing about historical fiction is that it allows you to concentrate on a single individual; and by seeing historical events unfold through their eyes, with all the fears, joys, hopes and emotions that involves, the reader may feel much more engaged and empathetic with the characters, and the story itself become far more memorable. The Endeavour voyage is such a great adventure … death in Tierra del Fuego, the seeming paradise of Tahiti, the warlike Maori, Botany Bay and near destruction on the Barrier Reef, the horrors of Batavia where a third of the crew died of fever. We Australians know only little bits of the tale. We deserve to know it all, for it’s one of our key foundation stories.

It was an account that I could have used in high school, to help piece some of the facts together rather than just being told what they are – is this something that good historical fiction should do for readers?

This is certainly the aim of good historical novels, and they can be far more entertaining for the general reader. Of course, we must always remember that the inner lives of the characters we write about are fictional and can only come from the author. We don’t know what they really felt and thought unless, like Cook or Banks, they kept full journals. For myself, I have always tried to make the external facts of my books as accurate as I can by reading, researching and travelling widely. I never alter a known historical fact to suit my story: the story must change to suit the facts. Where I have to make an assumption when the historical record is silent, I mention it in the quite full Chapter Notes. Yet I would hate to think that historical fiction would ever supplant traditional history which is grounded entirely on verifiable fact. Academic historians provide the real bones which writers like me clothe with fictional flesh.

In reading books like this and seeing history through the eyes of ordinary people who were also there, not just the ones whose names made it into history books, I feel it gives a well-rounded view of the history of a country. Is this something you hope to achieve when writing?

Yes, indeed. As I mentioned above, historical fiction writers attempt to humanise the past – to bring the characters in the academic histories to life using all the techniques available to a novelist. We have the advantage – denied to a traditional historian – of imagining the thoughts and emotions of our characters, together with the godlike gift of perfect hindsight and foresight which mere mortals never have as we live day to day through historical movements over which we have scant control. But of course, it is all fiction: my version of the Endeavour story may be quite different to the next one.

You dealt with Isaac’s interactions with indigenous people in a way that felt respectful – did these fictionalised interactions arise from imagination, from personal accounts of Captain Cook, or a combination of both?

I felt it important from the beginning to give a balanced account of the meetings between the Endeavourcrew and the indigenous peoples they encountered. It means including, as they say, a view “from the other side of the beach”. Cook’s instructions were to treat the native people with kindness – although it didn’t always work out like that. His first meetings with the Maori resulted in five or six native deaths, something he sought strenuously to avoid when he reached the east coast of New Holland and met his first Aborigines. I drew closely on the accounts of both Cook and Banks in their journals for my description of these events, and also had valuable insights from several Maori people, a Gweagal man from Botany Bay (Gamay) and Guugu Yimithirr people from the Cooktown area, who gave their perspective on these interactions and the misunderstandings that arise when any two quite different cultures meet.

When you were writing about the interactions of Cook, Isaac and the rest of the crew from the Endeavour, how conscious were you of how to portray these interactions to be fair and equal to both sides?

It was a very important consideration. For example, there was a clash over taking turtles between the Endeavour men and the Aborigines of what is now Cooktown, where the ship was repaired after striking the reef. From Cook’s point of view the sea turtles were there for the taking. From the Aboriginal perspective, the turtles belonged to them, and while they were happy for Cook to have some he should share them with the local people. The people I met impressed me strongly with the importance of the “sharing code” to this day: the culture demands you share food even with an enemy, for it might be you who’s in need tomorrow. I tried to reflect this in my account of the incident.

When you came to these sections, how important was it that you incorporate Indigenous and immigrant/coloniser narratives and stories, and what impact do you think this would have had on our history if this practise had happened from the start, as opposed to our current and historical approach?

As mentioned, it was important to try to incorporate both perspectives on these events … and to be fair, Cook and Banks and other members of the crew did try to understand something of the different cultures they encountered. They recorded many indigenous words for the first time – “kangaroo” entered the language from the Guugu Yimithirr, “tattoo” and ‘Taboo” from Tahiti. They recorded at great length different customs, beliefs and religious practices, especially in Tahiti. Banks and his scientists collected artefacts, weapons, items of clothing and veneration, and laid the foundations for what became the discipline of anthropology. To be sure these insights were often flawed (like their view of the turtles), but the intention was there. It would have been good if these high principles of the Enlightenment were adopted by everyone during the period after 1788; but under the imperatives of convictism, land, wealth, expansion, resistance and the use of force, they were too often forgotten, and we are still living with the sad consequences of that. But the British also brought their notions of political and economic liberalism and the rule of law, and the country became a free, self-governing democracy much sooner than might have been the case had some other nation become the colonisers.

How many years did it take you to first, research the book, and second, to write it?

I took about four years of fairly solid work from the time I began the first serious research to publication. I spent about 18 months gathering the material. It included four hours with Cook’s EndeavourJournal at the National Library of Australia in Canberra where I live, a 10-day sail on the Endeavourreplica from Melbourne to Sydney, which I loved and want to do again before I’m too old, and a six-week research journey to Sydney, North Queensland, New Zealand, Tahiti and the UK. The actual writing took about a year, with detailed research continuing throughout, six months for redrafting, and the last year with the editorial and production process.

What difficulties did you experience during the researching process in terms of available sources, especially any that might have been by or about Isaac?

The real difficulty was finding anything of substance about Isaac and his views of the great adventure. He lived to be 82, he was the last survivor, you’d think he’d have written something down for his posterity. But I could find nothing, and I was in contact with his direct descendants who provided information about the family but not Endeavour. Still, I did stay for three nights in the lovely house he built for his wife and family in Oxfordshire, and you can tell a lot about people — their taste and worldview — when you live for a little in the rooms they made for themselves.

How often was he referenced or spoken about in sources about the voyage and Captain Cook?

Isaac is not mentioned at all in Cook’s Journal, although he appears on the muster roll and in the pay books. Cook referred to him explicitly in a letter to the Admiralty when they returned in 1771 as one “whose behaviour merits the best recommendation.” His death was reported in the Gentleman’s Magazinein 1837, which states he was the last survivor of the Endeavourcrew. He is mentioned in Beaglehole’s definitive Life of Cook and in the annals if the Captain Cook Society, but until recently nothing of substance has been done on Isaac Manley. Now I have published Captain Cook’s Apprentice,and Isaac features in a book by Jackie French – The Goat that Sailed the World.

When writing your historical fiction, what do you find is most important – the facts and figures that inform your plot and research, or extracting the story and creating characters around these facts?

As I mentioned earlier, I regard the known facts as sacred. I never sacrifice them to the story: it is always the other way around for me, although I know other authors may take a greater licence with them. Perhaps it’s my background as a journalist. For me, however, when reading any novel that contains what I know to be a factual error, the whole artificial fictional edifice begins to weaken, and if it happens too frequently the structure will collapse and fall to the ground.

Captain Cook, as you mentioned in your author’s note, has been immortalised as great and humane navigator. Do you think this idea came through testimonies from the time, or interpretation of the sources by modern historians?

Cook’s greatness as a navigator was well recognised by his contemporaries. The Admiralty was so struck by the accuracy of his charts, his care for the health of his crews, that when Endeavourreturned they immediately set about preparing for a second voyage to the Antarctic to determine whether a great southern continent really did exist. It did: but so far south as to be uninhabitable by humans. And on his return, when Cook should really have rested, he was persuaded to undertake a third voyage to find the north-west passage over the top of America. It seemed too much. His judgement became increasingly severe and questionable, and ultimately, he was killed in an altercation with indigenous people in Hawaii. On his death, however, Cook became immortalised in popular culture no less than in the world of science and seamanship. Even today, you can place a satellite image over a chart of the eastern Australian coast mapped by Cook with his sextant and rule from the deck of a sailing ship, and the accuracy is remarkable.

Finally, what would you like to see future historians and authors of historical fiction exploring when they look into Australian history?

There are endless possibilities – and not just with new themes but finding new perspectives on an old story, as I did with Isaac and the Endeavour voyage. Tales from other voyages, the inland explorers, pioneering days, the great wars of the 20th century and more recent times can always be told afresh for a new audience. One significant theme of recent times has been relations between European and Aboriginal Australians. I’ve touched on it in several of my books, including Captain Cook’s Apprentice and especially The Burnt Stick. Relations between older Australians and the new wave of migrants and refugees is another important theme for contemporary writers. But really, I think it all depends on the story and the metaphors it contains. The tale is everything for an historical novelist: meaning comes afterwards. Do it the other way around – have a point of view and then try to find a story to fit it – and you’ll usually end up writing a polemic.

Thank you for joining me on my blog today, Anthony, and thank you also for writing such informative and interesting books.

Great interview.

LikeLike