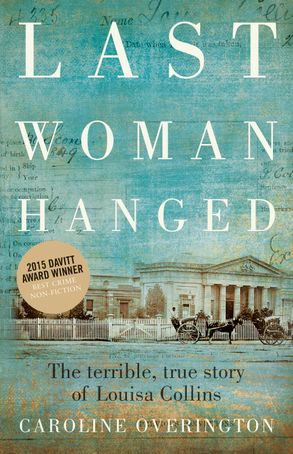

Title: Last Woman Hanged

Title: Last Woman Hanged

Author: Caroline Overington

Genre: True Crime

Publisher: HaperCollins

Published: 14th December 2015

Format: Paperback

Pages: 400

Price: $22.99

Synopsis: Two husbands, four trials and one bloody execution: Winner of the 2015 Davitt Award for Best Crime Book (Non-fiction) – the terrible true story of Louisa Collins.

In January 1889, Louisa Collins, a 41-year-old mother of ten children, became the first woman hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol and the last woman hanged in New South Wales. Both of Louisa’s husbands had died suddenly and the Crown, convinced that Louisa poisoned them with arsenic, put her on trial an extraordinary four times in order to get a conviction, to the horror of many in the legal community. Louisa protested her innocence until the end.

Much of the evidence against Louisa was circumstantial. Some of the most important testimony was given by her only daughter, May, who was just 10-years-old when asked to take the stand. Louisa Collins was hanged at a time when women were in no sense equal under the law – except when it came to the gallows. They could not vote or stand for parliament – or sit on juries. Against this background, a small group of women rose up to try to save Louisa’s life, arguing that a legal system comprised only of men – male judges, all-male jury, male prosecutor, governor and Premier – could not with any integrity hang a woman. The tenacity of these women would not save Louisa but it would ultimately carry women from their homes all the way to Parliament House.

Caroline Overington is the author of eleven books of fiction and non-fiction, including the top-selling THE ONE WHO GOT AWAY psychological crime novel. She has said: ‘My hope is that LAST WOMAN HANGED will be read not only as a true crime story but as a letter of profound thanks to that generation of women who fought so hard for the rights we still enjoy today.’

~*~

It is said that history is written by the winners, those left behind and those in power – and there is some truth to this. How many stories have been lost to us, how many accounts of events and different accounts have been lost to us because other groups and the other side has not been allowed to wholly contribute? As someone who studied history, there are many events and stories that I never learnt about in class and have often stumbled upon by chance through other reading and research. One of these previously unknown stories was that of Louisa Collins – convicted of murdering her two husbands after four trials, and in 1889, she became the last woman to be hanged in the then colony of New South Wales, after her hanging was a little more traumatic than it should have been.

In Last Woman Hanged, Caroline Overington looks at Louisa’s life before she was accused, her marriages and the events that led to each death, based on evidence and documentation that is available. As she observes throughout the book, the lack of Louisa’s own voice in letters or diaries illustrates the lack of power and agency women had in the colony of New South Wales during the nineteenth century. Indeed, each of the four juries that served on the trials were men from a specific class and professions – which Caroline points out limited the jury pool if certain professions could not serve – did this truly reflect a jury of one’s peers? Surely not, but Overington also acknowledges that this was how it was done – and whilst it is unusual for a modern reader, in the context of the history, it does make sense, though we may not like it one hundred and thirty years in the future.

What is interesting is that after the first trial ended in no conviction based on circumstantial evidence (which would be thrown out briskly these days, or efforts made to ensure it proved the crime beyond a reasonable doubt), the Crown ordered three more trials in an effort to come to a conclusion. It seemed that there was a determination to convict Louisa – with two dead husbands and ten children – some of whom were still at home and quite young – of a crime that she may not have committed. That circumstantial evidence was that both husbands had died of a rapid sickness, and there were traces of what appeared to be arsenic – a substance found at some of the places of work for men of the period, in rat poison and other areas around Sydney – and rat poison, such as the Rough on Rats used as evidence based on the testimony of Louisa’s daughter, May. Based on this evidence, Charles, her first husband, and Michael, her second, could have been poisoned anywhere – work, something that they ate or drank, or perhaps even medicine they ingested. Today, Louisa’s case would likely have been thrown out very early on if the only evidence was circumstantial.

Overington does more than examine the trials though – she looks at the beginnings of the suffrage movement and the impact that women like Liza Pottie had on trying to help Louisa – though these attempts would be futile and any evidence to suggest Louisa was innocent had had nothing to do with either death, or even just one – would come too late for Louisa, and further investigation, despite pleas from women who backed Louisa and eventually, Louisa herself.

History tells us that Louisa was without a doubt guilty – four trials were conducted just to reach that verdict, and one wonders why – if nothing could be proven, the charges were not dropped as one might expect them to be in other cases. It feels like the lingering question is why – why were people so bent on convicting Louisa on circumstantial evidence? The Rough on Rats could have been used for any reason, such as killing rats, but also, could have been accessed by anyone in the house – not just Louisa. We will never know why these questions were not asked or looked into further – it might have saved a woman’s life.

Whether she was guilty or not cannot be determined now, nor can we change the past – the charges, and execution or the way Louisa’s case was handled with inadequate defence – by not questioning the validity of the circumstantial evidence, Louisa’s fate was sealed. This is an intriguing read, about part of Australia’s history not often taught in courses, and one that has to be sought out by those seeking to learn more. Hopefully, this will allow more stories of those silenced in the records of history to be told – and in doing so, will allow for a more well-rounded historical record that shows the complexities and grey areas of history, not just the black and white we see so often.

Excellent review Ashleigh!

LikeLike

Thank you! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great review, although one wonders whether we have really improved the legal system that much – the Lindy Chamberlain story is a case in point. There are also others being looked at now where the evidence is quite weak but the convicted person had other societal issues. At least we do not hang people anymore!

LikeLike